David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York (42nd Street), 1978-79.

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York.

Used with permission.

The first time I visited New York was in 1979. It was my first time in America and I went, along with Araki Nobuyoshi and his wife Yoko, for the opening of the exhibition "Japan: A Self Portrait" at ICP. My first impression of New York at the time was that it was dirty city. Garbage was dumped in the alleys between skyscrapers and the air seemed to be polluted. When we changed planes in San Francisco on the way, we had enough time to spare to go downtown before the connecting flight. But in San Francisco it we hadn't suffocated by the air. I was only in New York for a brief time but I was shocked by the bad atmosphere that soaked this city where everyone dreamed to be.

The exhibition venue was in a quiet part of uptown Manhattan, in an old brick building. After the opening, Yoko went to Argentina, where her mother was living, leaving Araki and me to roam around the city. On 42nd Street we looked at photos on the peeping machines for 25 cents, watched the porno Taxi Girl, and ate at restaurants. At night, we'd go to jazz bars around town where the darkness got darker. We strolled all the way to Harlem to take pictures but we didn't once feel afraid. That's because it was always the two of us, a man and a woman, a couple. However, after Yoko came back to New York, the Araki and Yoko returned to Japan, and as soon as they left, as a woman alone in New York in 1979, they had many horrible experiences and suffered discrimination that I can't ever forget.

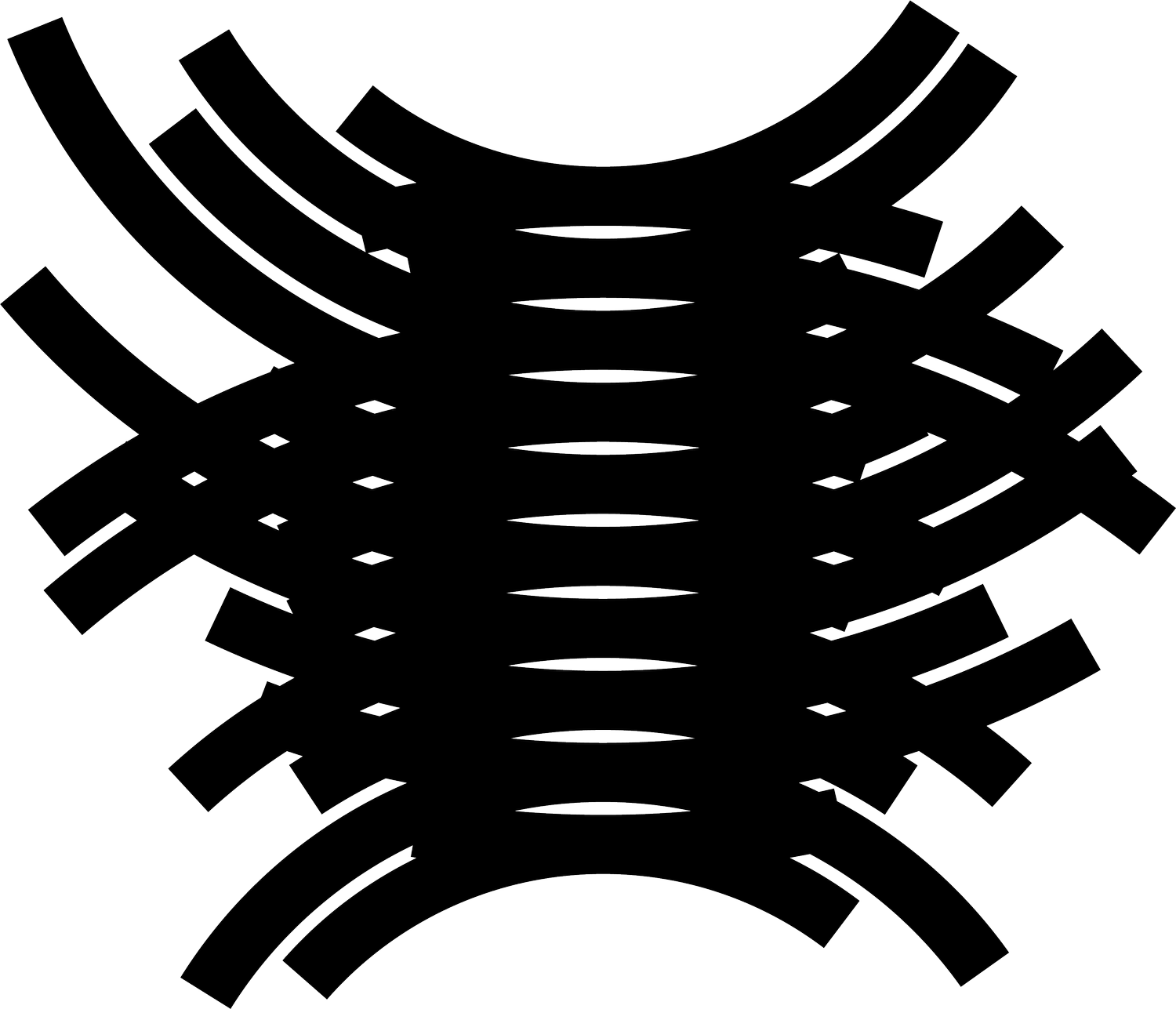

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York (reading newspaper), 1978-79.

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York.

Used with permission.

Since then, I've been to New York countless times, and every time I go there, New York becomes a cleaner and safer city. In 1996, I stayed in the city by myself for about three months and rarely felt afraid or discriminated against. And in 2018, when I was in Chelsea for a week preparing for a solo show at a gallery there, I visited the newly relocated Whitney Museum of American Art and saw the exhibition "David Wojnarowicz: History Keep Me Awake at Night." I knew very little about him except that he died of AIDS and that I had seen his picture of Peter Hujar's deathbed at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. I became frozen in front of one photograph. What is this?? In this slightly out-of-focus 35mm snapshot, a lanky man wearing a mask almost blending into the background of the New York landscape. He has lunch at a restaurant. He's on 42nd Street. Standing in front of a peeping show machines. In front of graffitied walls. He rides the subway. Sometimes he's got a cigarette in his mouth. He shoots up. Jerks off. Picks up a gun. The masks are all of the same man's face. Sometimes the mask slips to the side, or it's at an angle completely different from the direction of his body. The imbalance of body and face's (mask) position is strangely erotic and exciting. This was "Rimbaud in New York," I learned. The mask was the face of Arthur Rimbaud. A Frenchman from 100 years ago shows up in New York and gets photographed here and there. The reflection of the white face of the figure is painfully sad and humorous, emitting a strong poisonous atmosphere into the void.

I was struck and riveted to the place by the strong force of imagination that Wojnarowicz chose Rimbaud and became Rimbaud, revisioning New York of 1978-79; the power of his imagination was printed in the photograph as a grave gaze that was a blow to my chest, riveting me in the spot where I stood.

"Rimbaud in New York" reveals the essence of photography, brilliantly breaks with the photographic conventions of documentation, transcends time and space with ease, plays the line between truth and falsehood, photographs the moment of communion between the body as an entity and the human body of the past buried in history, and thereby creates an eternity.

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York (tile floor, gun), 1978-79.

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York.

Used with permission.

Wojnarowicz and Rimbaud are from different times, but the meaning of life and its relationship to death, and their radical and series thoughts on love are two sides of the same coin. Rimaud at 37, Wojnarowicz died at 38. Two men who, in the course of their short and intense lives, overlapped and resonated, leaving behind in these photographs a definite mark of life. And 40 years on, I receive them.

"Rimbaud in New York" reveals a number of issues in photography. Wojnarowicz knew to watch out for the peculiarities of photographic expression that are involved in the photography function to fix the past. This work expresses the meaning of essential photography. When I leave the museum thinking that in 1979, the same year I was in New York, I never met Wojnarowicz and I may have crossed paths in front of that 25-cent peeping machine.

The next day, in a state of considerable excitement, meet up with Andrew Roth. Of course, we spoke about "Rimbaud in New York." Then he casually brought out a photo book with a light blue cover and a Rimaud mask printed on it and gave it to me. It was the book Rimaud in New York that he published in 2004. There were many photographs in the book that weren't in the Whitney show. I was amazed and delighted, and I was reminded of Roth's approach to publishing, the quality of his work and his good taste.

Meeting an artist gives me great strength. From Wojnarowicz's work, the image that I could extract was, in a grand sense, the direction of love's intention and the problem of communication between people.

The New York of 1979 appeared to me like a miracle in 2018. The past is always in the present and the future always in the present. We have to make sure we don't miss that. And I am grateful to have met David Wojnarowicz and to experience the sharing of the infinite in photography itself.